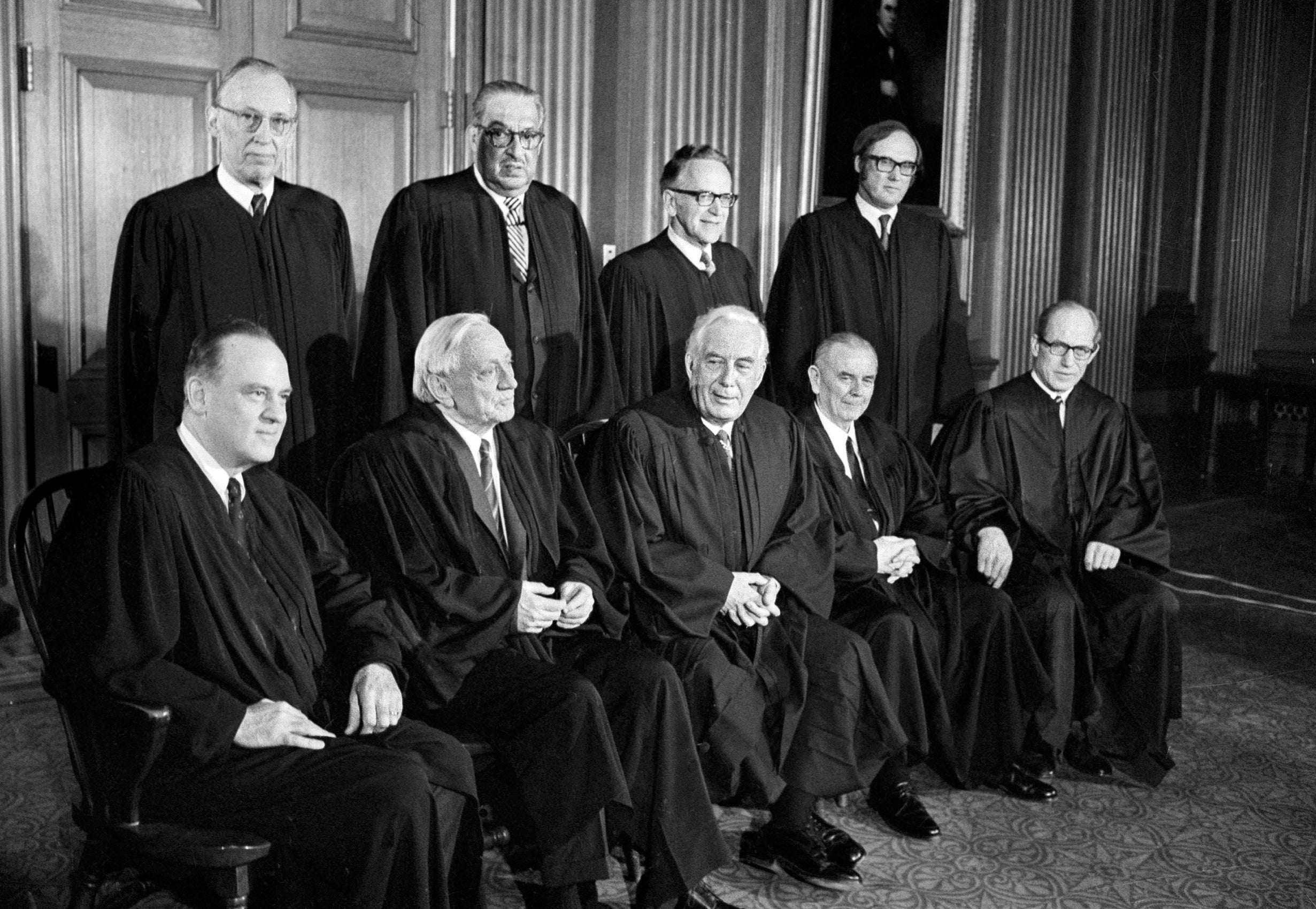

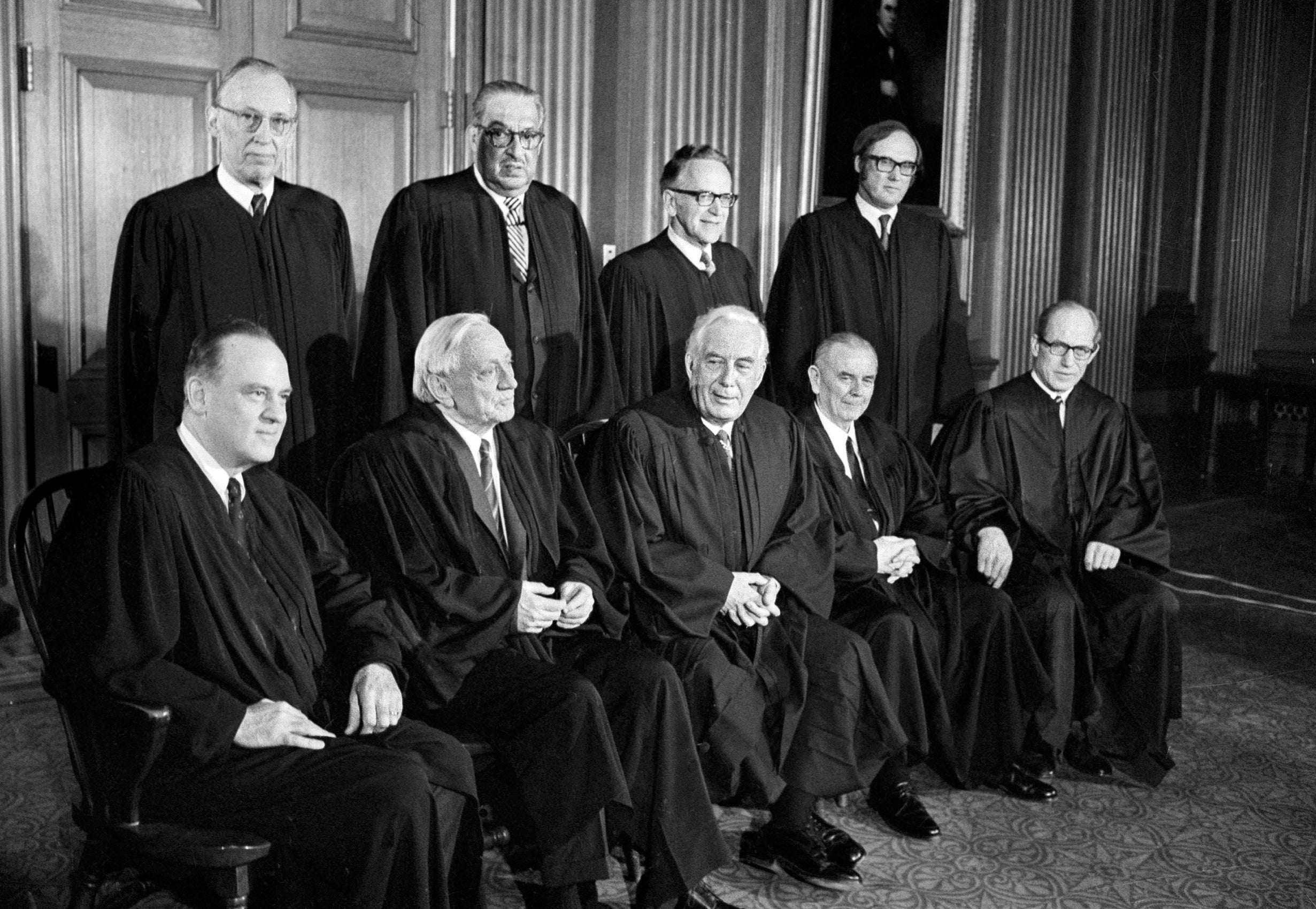

portrait of justices of the Supreme Court" />

portrait of justices of the Supreme Court" />

portrait of justices of the Supreme Court" />

portrait of justices of the Supreme Court" />

More than 50 years ago, the U.S. Supreme Court held in Furman v. Georgia that the death penalty was an unconstitutional violation of the Eighth Amendment ban against cruel and unusual punishment. With that, 629 people on death row nationwide had their capital sentences commuted, and the death penalty disappeared overnight. “Furman was a remarkable intervention,” says Jordan Steiker, a professor at the law school at the University of Texas at Austin and co-director of its Capital Punishment Center. “Even though it was quite short-lived in suspending the death penalty in the U.S., it completely changed its course because it essentially inspired or required states to rethink how they were doing capital punishment. And ultimately, the practice of the death penalty changed substantially over time.” Given the greatly heightened public attention to the power of the Supreme Court today, the 50th anniversary of Furman is an opportunity to reexamine not just the history of the death penalty but the appropriate role of the Court in American life, Carol Steiker and others believe. “Right now a lot of people are wondering how much of a role we want the courts to play in deciding what rights are guaranteed by the Constitution, and Furman v. Georgia is a unique example of when the Court struck down a policy that was widely prevalent throughout the states for violating the Constitution,” says Gene Young Chang ’24, who has been studying the death penalty with Steiker since he was a freshman in her Harvard College course The American Death Penalty: Morality, Law, and Politics. Furman, he says, “teaches us things about the role of the courts in a democratic society, the scope of constitutional rights, and the proper method for defining those rights.” Categorical abolition of the death penalty across the nation is unlikely without another Furman v. Georgia, “what you might call Furman II, which is obviously not forthcoming from this Court or anytime in the foreseeable future,” Carol Steiker says. Instead, the future of the death penalty, she says, is being played out at the local level, in “a kind of guerrilla war going on county by county, state by state, with the election of progressive prosecutors who do not seek the death penalty, state legislative activity, and state constitutional litigation under state constitutions.” The final death knell for capital punishment will likely depend on a very different Supreme Court from the one we have today, she says. “But at that point,” given other trends in the country, “it may be more like a coup de grâce rather than what it was at the time of Furman.”

In the 1960s, due to a campaign by the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund to challenge its constitutionality in cases across the country, capital punishment was in decline. Indeed, no one was executed in the five years before Furman, as states waited to see what the high court would rule. In 1971, the Supreme Court rejected a due process challenge to capital punishment. But Furman, argued a year later, relied on the Eighth Amendment: The LDF team argued that the arbitrary application of capital punishment — jurors, often with no guidance, had complete discretion on when to impose it — was a cruel and unusual punishment.

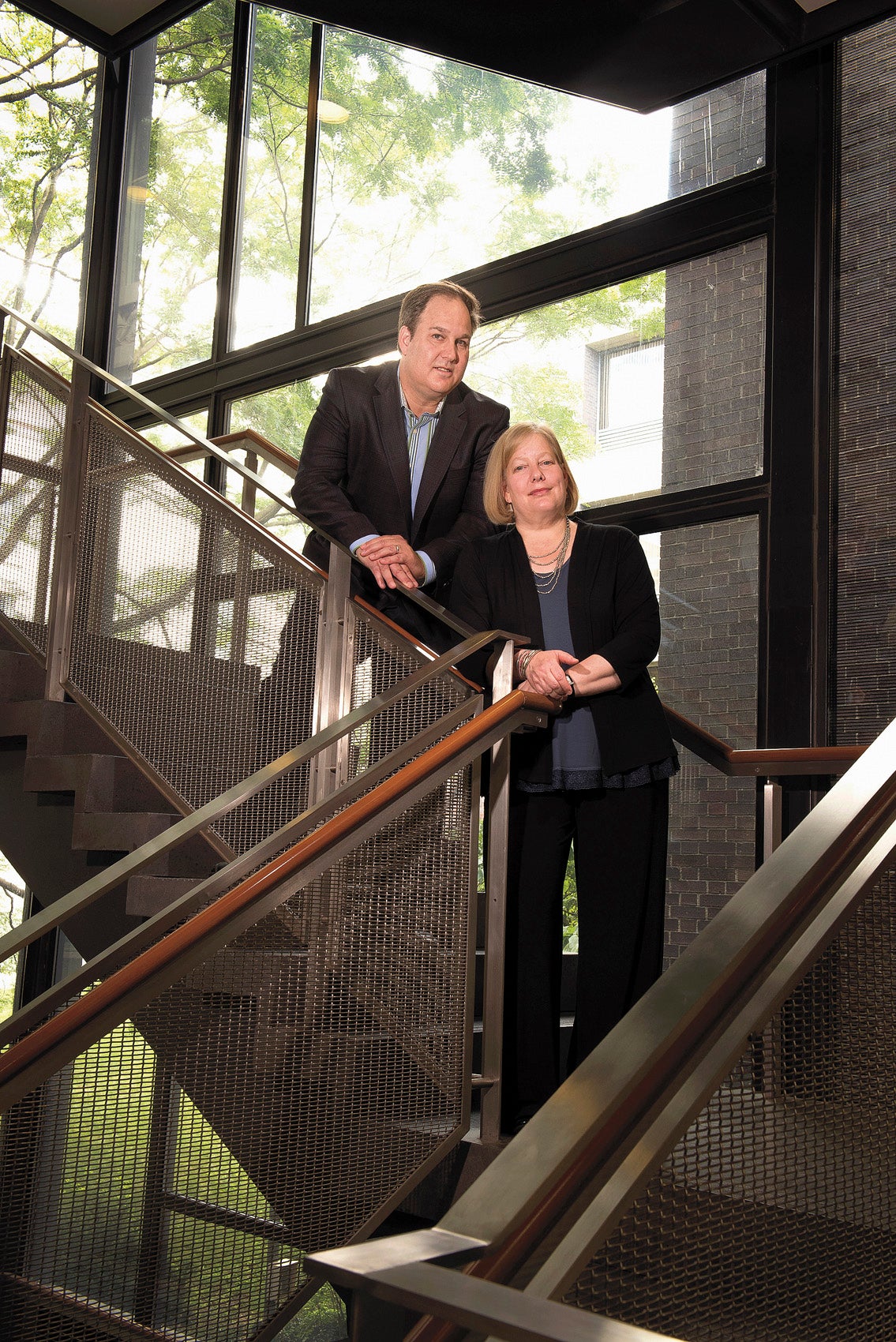

Carol Steiker teaching in a classroom" />

Carol Steiker teaching in a classroom" />

In the end, then, was Furman a victory for those who brought the case? “That’s a good question,” says Jordan Steiker. “There’s one point of view that I’m sympathetic to, that says that Furman revived a practice that was dying on the ground, and had there been no intervention, we might not have had a revival and then a second decline.” On the other hand, when Michael Meltsner, one of the lawyers on the LDF team who brought Furman, speaks to Carol Steiker’s capital punishment class each year, he emphasizes that there were 629 people on death row in 1972 whose lives were saved by Furman. “So in that sense, it was a tremendous victory,” says Carol Steiker. “It was a reset moment.”

Video: Steiker discusses the 1972 landmark Supreme Court decision that declared the death penalty unconstitutional.